Thanks to Ian for the invite and the reminder nudge. Hopefully this will just squeak in before the deadline, as my department is currently interviewing a new head which has consumed my time of late. This has had one significant benefit: spending serious amounts of departmental cash on taking candidates to expensive restaurants around town, and to do some consuming, participant observation, and thinking all at the same time.

My first comment regarding Ian’s intriguing and challenging progress reviews, and this excellent and rapidly proliferating blog, is regarding the role of restaurants. They are simultaneously great and poor places to reflect on ‘mixing’ and ‘following’. Great, because of the wide variety of food ingredients and preparation methods that are embodied, and because the close hubbub of humanity lends to interesting evesdropping on conversations on and around food. Poor, because most ingredients, and indeed many preparation methods in most (but not all) restaurants, are hidden from actual view, and so ‘things’ are not so easily ‘followed’. Wine lists are invariably great places to trawl the globe, but menus rarely mention the origin of food, unless it’s some signature piece (Loch Fyne salmon, Prosciutto di Parma, and Bluff oysters come to mind). Some restaurants quite deliberately bring the food preparation into customer view, such as the theatricism of Teppanyaki (which got a mention in ‘Mixing’), Mongolian barbeques, and Brazilian churrascaria, but for most we can only vicariously experience the culinary show through Gordon Ramsey and a multitude of other food ‘reality’ TV. This is important because of the increasingly out-sourced nature of food preparation in many households over the last decade, reducing the opportunity for these households to make more informed choices about the origins of their meal ingredients, beyond choosing the type of restaurant. Interestingly, McDonalds is a standout among fast food chains for highlighting through TV advertising the local origin of its ingredients, at least in New Zealand (pickles apparently being the only exception to NZ sourcing). If only their foods weren’t so poor in what they mixed together…

I liked the two vignettes Ian opened and closed ‘Mixing’ with, though their similarities struck me more than their differences, particularly on the notion of authenticity. I am reminded of an ad for Patak’s curry sauces that is currently running in New Zealand, with the tagline “straight-up Indian”. The TV ad is overdubbed from its original language (unknown, but the audience is meant to presume it is ‘Indian’, judging from the music and appearance of the actor) with a country-bumpkin Kiwi accent. This perhaps signifies three things: the supposed authenticity of the product; the pseudo-sexual imagery implied in the tagline; and the pastiche of a budget ad in the knowing style of asynchronised Japanese-American overdubbing, positioning the brand as authentic but inexpensive. Authenticity is a theme I see running through many of the blog entries, be it fairtrade (real income support to the people that matter?), organic (really better for the environment/worker/health of consumer, or simply a segmentation strategy to extract greater margins?), local (carbon footprint vs trade-aid?), as well as the whole discussion around bell hooks’ “eating others”.

Third, food is frequently bound up in notions of nationalism as well as ethnicity; we eat countries as well as ethno-cultures. There is nothing “more American than apple pie” (or “Tex-Mex” or Twinkies or doughnuts); Greece is Tzatziki (and the salad); Japan is sushi; and the New Zealand signature desert is Pavlova (with Kiwi[fruit]), although such assertions tend to infuriate Australians who nefariously claim it as theirs. Fusion food may try to blend these “national signifiers”, and their significance is often shallow or regionalism transcended (witness chicken tikka masala being recognised as Britain’s national dish – see Collingham, 2006; and Robin Cooke’s famous speech in 2001). In my reading of Ian’s pieces, the notion of (ethnic) food is couched in positive terms, and it is the language around food that needs working on (similar to Gibson-Graham’s (1996) notion that the language available to describe the economy in part determines the kinds of economy that can exist). But what happens when the food itself is contested: whale, dog, cow (in India), horse (for pets or humans), let alone alcohol in the middle east? Henry Buller’s blog entry discusses animal vs food geographies, but more could be made of this treacherous ground, I feel.

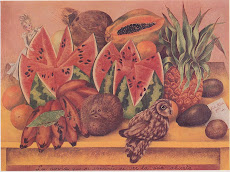

I take heart from the blog discussion and Ian’s mentions in both papers the disquiet that surrounds the producer-consumer linkage and the “missing consumer”. Ian notes that many commodity chain studies progress from the producer/worker only so far as the retailer, and often not even that far, whereas consumption studies often link retailer to consumer, but not further backwards (see for example Danny Miller et al, 1998), and consumption studies reviewed by Louise Crewe (2001, 2003) and Jon Goss (2004, 2006). The BBC documentary Mange Tout did this to a limited extent, looping back to a middle-class dinner party and tracing links to producers/workers in Zimbabwe (see a UK student’s blog on the doco here: http://jamesomalley.co.uk/blog/2005/11/mange-tout), but that is a rare example. It’s not producer-consumer links we need to worry about, so much; it’s crossing the retailers (in both directions, and both meanings). While Ian’s (2004) “Follow the thing: Papaya” paper included an end consumer in his wonderful exposition, ‘Emma’ was borrowed from another project, and did not herself directly consume the fruit (though the ‘sting in the tale’ was the number of products she was unknowingly consuming that might contain papain extracts). Not always ‘missing’, then, but definitely muted. Can’t consumers shout, in the way that Mike Goodman is accused of? Would we want to hear them if they do?

Kersty Hobson, David Nally and Louise Crewe all blog that the consumer cannot / should not be loaded with responsibility for solving ethical problems in food supply, since this privileges the rich that can and absolves corporates from their moral duties. David Nally’s quotation from Felicity Lawrence’s new book (Eat Your Heart Out) is quite telling: “… Then the supermarkets will be able to say ‘Ethics? We just do what our consumers want.” Of course this is what supermarkets already do: Tesco is not a charity, and consumers are (mostly/often/occasionally, depending on their location) free to choose other sources of their food with different ethical approaches, albeit not at Tesco prices (witness the Whole Foods Market in London). This is a present reality, not a future nightmare scenario, and consumer choices DO matter, even if the politics of this is not always explicit, and choices are inherently constrained (it is difficult to signal to a Tesco supermarket which products you would like to buy that are not currently stocked, though this demand signalling is more effective with online shopping as failed searches are recorded).

Ian no doubt asked me to participate because of my status as a refugee: a lapsed (food/retail) geographer, now in exile in a business school in the antipodes. Perspective and context do matter, and teaching consumer behaviour and going to marketing conferences has altered my perception of the ‘dark arts’ of food marketing. While I miss wandering down Birmingham corridors to chat with Ian (though he has since exiled himself to the wilds of Devon), I am enjoying the renaissance within marketing of its social uses and greater reflexivity of its impacts, and the increasing importance of qualitative methods, particularly ethnography.

In “following the thing”, what Ian and others mean (or at least do) is following a product from point of production to some end-point down the supply chain. In the other direction flow money (rapidly reducing as intermediaries clip the ticket) and value (likewise, as most value added at retail sale comes from the retailer’s assortment of like products at a location convenient to the consumer, taking the risk of spoilage and theft, as noted in Ian’s (2004) Papaya piece). Louise Crewe’s post notes the disconnect between these: consumers that “know everything about price, but nothing about value”. Marketers (in the “real world” sense) make this disconnect their business, because if the link between value and price is obfuscated, then margins can be improved, as a cost-plus markup is replaced by “what the market will bear”. Consumer behaviour research suggests that consumers are increasingly aware of this game. But marketers are also aware that consumers are aware, which consumers are in turn increasingly aware of… This circuitous reflexivity of course leads to the designer / Primark jeans conundrum that Louise discusses, where consumers have little idea whether a luxury brand is more expensive to produce or just a basic product with incredibly fat margins, and so might as well start with the cheapest, with ramifications back through the supply chain.

I intend this discussion to note that there are many “things” that can be “followed”, not all of them tangible like papayas or French beans, from different starting points. Because of the signalling power (if not truly emancipatory power) of consumer choices, starting from the consumer and working back through the retailer/market to the producer/worker is as valuable theoretically and politically as the reverse, and something I am attempting to do for organic foods (in NZ, and the UK to Dominican Republic, with Amy Trauger), and for ethical consumption more generally (NZ). Farmers markets of course shorten and simplify these links dramatically, as Moya Kneafsey et al (2007) found out in the UK and I am discovering in NZ, but their small scale also reduce their political significance.

There is at least one benefit of an antipodean exile: the excellent annual Agri-Food Research Network conference, which brings together a truly multidisciplinary audience as well as practitioners. The next is in Sydney in November – see http://www.geosci.usyd.edu.au/news_events/afrn08/index.shtml for details.

References:

Collingham EM (2006). Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors. Oxford University Press

Cooke R (2001). Speech to Social Market Foundation, extracted in The Guardian, April 19 2001.http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2001/apr/19/race.britishidentity

Crewe L. 2000. Geographies of retailing and consumption. Progress in Human Geography, 24(2), 275-290.

Crewe L. 2003. Geographies of retailing and consumption: markets in motion. Progress in Human Geography, 27(3), 352-362.

Gibson-Graham J.K. 1996. The end of capitalism (as we knew it). Blackwell, Oxford.

Goss J. 2004. Geography of consumption 1. Progress in Human Geography, 28(3), 369-380.

Goss J. 2006. Geography of comsumption[sic]: the work of consumption. Progress in Human Geography, 30(2), 237-249.

Kneafsey M, Holloway L, Cox R, Dowler E, Venn L, Tuomainen H. 2007. Reconnecting Consumers, Food and Producers: Exploring Alternatives. Oxford: Berg.

Miller D, Jackson P, Thrift N, Holbrook B, Rowlands M. 1998. Shopping, Place and Identity. Routledge, London

Murphy AJ, Trauger A. 2006. On the Moral Equivalence of Foods: Organic and 'Conventional' Bananas in Global Production Networks. Massey University Department of Commerce Working Paper Series 06.06 / SSRN working paper (http://ssrn.com/abstract=1068404)

Friday, August 29, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment