Forgive me this personalised sketching and its use of a rather extended metaphor- it is designed merely to inspire thought. I hate fancy dress parties, but as a close friend of mine was turning 40 there was no getting out of it. The theme was ‘heros and legends’, and after much somewhat tetchy discussion and research (?!) I settled upon Carmen Miranda. I have no idea why, apart from the fact it was not too obvious, it would not cause me to look unattractive after a few drinks, and she was only 5 foot tall- which gives me a whole 2 ½ inches over her.

Forgive me this personalised sketching and its use of a rather extended metaphor- it is designed merely to inspire thought. I hate fancy dress parties, but as a close friend of mine was turning 40 there was no getting out of it. The theme was ‘heros and legends’, and after much somewhat tetchy discussion and research (?!) I settled upon Carmen Miranda. I have no idea why, apart from the fact it was not too obvious, it would not cause me to look unattractive after a few drinks, and she was only 5 foot tall- which gives me a whole 2 ½ inches over her.Carmen’s famous headdresses were based upon those of the Bahianas- the female fruit sellers that were so much a part of her working class childhood. The image of the Bahianas is still an iconic one within Brazil today, albeit not whole-heartedly embraced. It is perhaps seen as too comic a depiction of the working class; it perhaps tends to err on the side of camp a little too heavily; it is perhaps a little too inseparable from the later images of Carmen that caused her to be accused of having become an ‘Americanized’ caricature of herself, and led to her being practically disowned by Brazil. The song ‘Bananas is my Business’, from the film ‘The Gang’s All Here’, was a direct attempt to address these complaints.

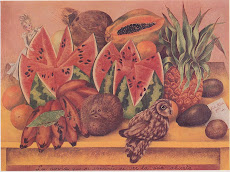

Unlike Carmen’s expensive creations, my headdress is built up from plastic fruits and flowers, feathers and beads purchased in the pound shops along Deptford High Street, London. As it gradually takes shape, this great assemblage of consumption, begins to cause me increasing concern. For the same reasons Brazil disowned Carmen for consuming and using a cultural image, part of me wants to disown myself for consuming and using the image of Carmen using the image of herself using the images of… you get the picture. If Carmen was allowing the US to ‘eat the other’, (see Ian’s ‘Mixing’ article) then I am eating that which made the other edible. I’m pretending that bananas can be my business too, when it suits me. But then, is not that inevitably what one does in fancy dress? My friends say I’m reading too much into it- it’s just a party. They are right of course, but that’s not the point.

The thing is bananas are my business right? And yours. And everyone’s. Isn’t that what we’re trying to do in exposing the journeys of such things? Get people to think about where things come from? Get them to have the kind of ‘embodied’ experience Ian mentioned in the ‘Following’ piece? Get them to feel, and care, and take responsibility? Sure. I guess we are. But how to do this without it being simply a consumer movement, and a rather preachy one at that? Taking responsibility is, in this case, the luxury domain of the well-off. As Louise Crewe says, consumer-based responses can indeed be ‘socially divisive’.(2001: 631) It is not that I am against fair-trade by any means, it is simply that I recognize it as something that only the better-off can indulge in. Ethics are inexpensive for middle class shoppers. And supermarkets know how to make a decent profit out of selling them. Hobson’s point in the ‘Following’ piece is a good one- the responsibility and behavior change needed to redress inequalities of supply chains is too heavily laid at the door of the consumer, when governments and large corporations should be taken to task. (Hobson, 2002)

In many ways this question as to who should feel the greater responsibility echoes the concerns of trying to map the whole ANT versus Marxism conundrum. Both attempt to expose the traversals of products for the same reasons; it is the ‘what is to be done’ part that separates them. Which leads us to the thorny question of boundaries, mentioned in the ‘Following’ piece. What I shall continue to call ‘thing following’ (as opposed to Global Commodity Chain analysis, which far too frequently assumes poles of ‘north’/’south’, consumption/production) needs badly to give itself some boundaries and a clear raison d’etre if it is to withstand the criticism leveled at it. By boundaries, I do not mean defining what is followed, how, by whom, where, etc (although we do need to maintain an awareness of potential self-indulgence). I do not even mean that any historical disciplinary colours need be nailed to the mast- like Crewe (2003) I would agree that attempting to combine theoretical traditions is of little interest and may be of little use. No, what I mean, is the why? The key to thing following is in the issues.

Perhaps one of the issues worth considering as an on-going theme/focus for thing-following is duration. During my shopping for Carmen’s headdress I kept thinking how wrong it was that the plastic fruit was cheaper than the edible ‘real’ thing. It put me in mind of Hannah Arendt’s comments in The Human Condition:- ‘All things really necessary for man to survive are of short duration. They disappear quickly and are the most natural of things.’ (1958:96) So does it follow that the opposite is true- things of long duration are the least necessary? Perhaps so. But Arendt’s comment here is one concerning the fundamental nature of humankind in terms of basic survival; it is not meant to uncover the ways people make ends meet in market systems and as part of complicated networks. The truth for our purposes is in the chain. Only a revealing of the complete chain can lend an understanding of how ‘necessary’ any one product is to all those involved in its making. You may not be able to eat plastic apples, but in what I would call survival capitalism, (put briefly, a capitalistic system or network which requires one actor by necessity to exploit another in order to survive) the way one plays the chain in order to earn a living can be a matter of life or death. And one of the key factors that decides this battle, is duration.

In Arendt’s sense a plastic apple is of long duration and relatively useless; it will lie in landfill for decades before being completely decomposed, yet its life-span before being trashed is very short. This is key. What has become necessary for survival across the chain is an increase in both the geographical length and the depth (i.e. number of ‘hands’) of supply chains, and a decrease in the commodity’s duration (before being trashed). In short, survival has become inextricably bound-up with consumption, even in the so-called ‘production poles’ of the world. For example, the Chinese government is now encouraging its people to consume more, as they need people to trash commodities in order to gain valuable raw materials for production, rather than having to buy waste from Europe and the US. We have known for a long time that consumption must eat itself- the notion of the ‘good consumer’ is no stranger to news headlines. But now production must also consume. Consumption emerges as the sole answer.

There are two reasons for concern here. Firstly, the consumption-based solution is fundamentally flawed. It is pathological. It attempts to find the answer to its problem in the problem itself. Secondly, and linked to the first, it demands of us merely that we slightly change our habits, that we shop in a slightly different way, buy slightly different things. As such, it is doing precisely what makes capitalism so strong; it allows it to survive by internalising its worst enemies, its fiercest critiques, and so to exist in a state of profitable (for the few) pathology. Arendt again:- ‘…our whole economy has become a waste economy, in which things must be almost as quickly devoured and discarded as they have appeared in the world, if the process (of production and consumption) is not to come to a sudden catastrophic end.’(1998:134) If this is true of ‘durables’, the implications for food production, as we know, are far-reaching and of immediate concern.

I have come a long way astray from Carmen. I have probably come across as anti-consumption- which would be a gross over-simplification. I hope I have highlighted my slightly dubious attitude towards fair-trade and underlined a possible mission for thing-following- to find an alternative to ‘the good consumer’, which can only ever be a moneyed capitalistic response. By way of conclusion I can only offer questions. Are attempts to shorten supply chains, for example with home grown vegetable initiatives, valid, or is this simply avoiding the global issue by reverting to the local? Do fewer hands necessarily mean better ethics? How can we map what is ‘ethical’ across any given chain with its intricate and specialised scenarios? Is the answer to increase practices of agglomeration (rather than conglomeration), in an attempt to share opportunities between as many players as possible and disallow large corporations control? How do we suggest a fundamental change in consumption practices without coming across as simply anti-consumption?

Maybe I was simply ‘getting with the fetish’, to use Taussig’s phrase, (1992, quoted in ‘Following’ piece) in my Carmen headdress. Is getting with the fetish of any more use than attempts to de-fetishize by exposing the chain? Couldn’t both arguments be accused of fetishizing the fetish?! Somewhere in here, but by no means well enough formed in my mind yet, there is something about value emerging as an answer. A value that goes beyond the (de)fetish and seeks to discover how any one product is embedded in networks of action, creativity and imagination It is perhaps poignant that Marx defines use value as ‘needs of the stomach and the imagination.’ (1976: 125) Food is the raw edge of thing-following analysis. Bananas is everybody’s business.

Alison Hulme. Posted 13/8/08

Appadurai, A (1986) The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge: CUP

Arendt, Hannah(1998) [1958] The Human Condition. Chicago: UCP

Crewe, L (2001) ‘The Besieged Body: Geographies of Retailing and Consumption’. Progress in Human Geography 25, 629-40

Hobson, K (2002) ‘Competing Discourses of Sustainable Consumption: Does the rationalization of Lifestyles make sense?’ Environmental Politics 11, 95-120

Marx (1976) Capital, Vol . London: Penguin

Taussig (1992) The nervous System. London: Routledge

No comments:

Post a Comment